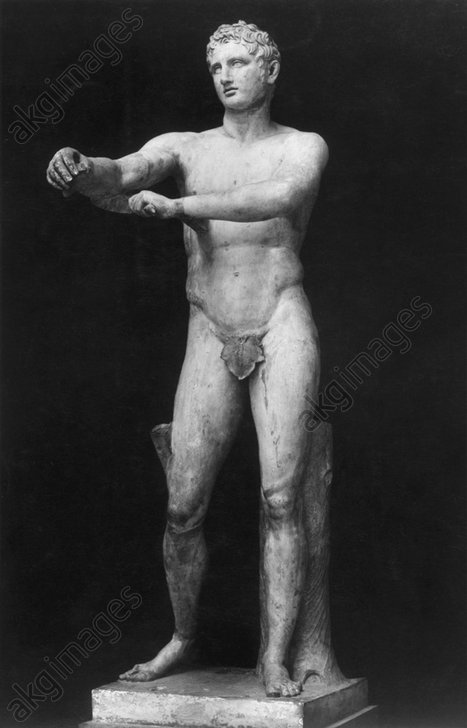

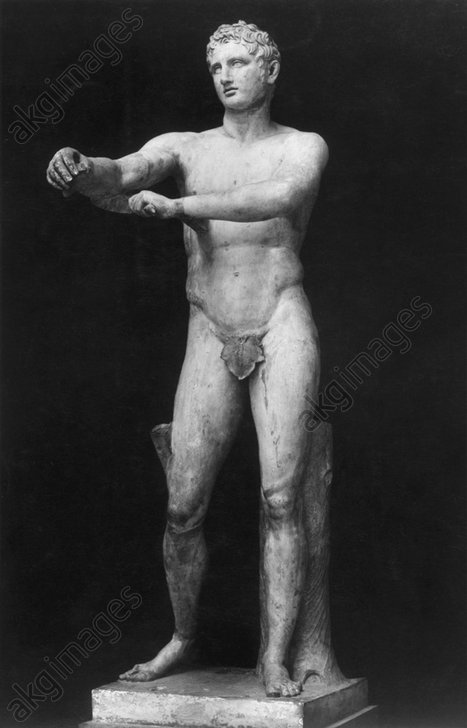

Apoxyomenos by Lysippus

GREECE, THE CRADLE OF WESTERN CULTURE

Jordi Rodríguez-Amat

Early February 2002, I embarked on a trip to Greece. Greece had been dancing around my head for many, many years. Since the years when my awareness of cultural values awoke in me, the knowledge that I was gradually gaining from the origin of Western culture attracted me to that country. Not in the same way that I was interested to other countries, especially Asian ones like India, but with a meaning very close to us; Greece as the cradle of our culture. I, like the Western world, stared at that civilization. |

|---|

Although there were few at the Liceo las Artes of Josep Alumà in Barcelona, the school where I took my first steps in the world of drawing and painting, I was able to draw some Greek, classical and Hellenistic sculptures. They were small-format copies made of plaster. Later, in September 1960, in the entrance examination to the Barcelona School of Art, I had to draw the Apoxyomenos by Lissippos. The exam was held in the classroom where the so-called Ancient Drawing was done. There were many plaster copies of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, and every time you entered that classroom, you were immersed in a classical world filled with a model aesthetic for all of us. It is clear that the plaster is apathetic, dispassionate and manifests itself stripped of the warm coldness that maintains the burst and the diaphanous cleanliness of marble. However, the spirit of the forms, the classical proportions, the balance and so many other aesthetic values that, even at that time prevailed in the studies of that art school, transported us to a rich world of pure beauty.

Apoxyomenos by Lysippus |

|

|---|

My artistic training followed the principles established in the art schools of the time and the classical world, with all its aesthetic contents of beauty and proportions, which anchored the ship of the art evolution to doctrines supported by the Greco-Roman world, a world nuanced by centuries of Renaissance reflection. Something that helped to increase my desire to know Greece was a small talk given by Francesc Artigau, a colleague of the Fine Arts School, at the headquarters of a students trade union created by Franco's regime, whose sole purpose was to control the university world from the totalitarian power of the dictatorship. The headquarters of this trade union were located in Canuda Street in Barcelona, not far away from the Barcelona Athenaeum. Francesc Artigau had finished his Fine Arts studies a year before me and during the summer he went on a trip to Greece. Neither the magnitude of the trip nor the characteristics of what he told us remains in my memory. I just remember that, assisted by some very plain explanations, he showed us some slides and some drawings he had made during his trip. What really sparked my desire to delve into Hellenic culture was the reading in the fall of 1965 in Paris of a book by Henry Miller entitled The Colossus of Maroussi. I read it in French, because at that time I did not have the ability to read texts in English with a certain difficulty. Now I don't remember if it was me who bought it or it was given to me. In any case, it was recommended to me. Today the details of the book are no longer clear, not even the places described, what remains are the memories of the feelings that its reading generated in me. The journey through the different places of Hellenic geography, the experiences lived by the author, the encounters and everything that the book describes created in me the passion to, one day, delve into it personally. Years later, around 1984, I read Tropic of Capricorn, another book from Henry Miller. It is an eccentric book full of nymphomaniac women. An exciting and successful book, wild and powerful, one of those books that are impossible to quit halfway through reading. Reading a book can provoke sensitive states generated by values inherent in the work and independent of simple descriptive narration. Then, the memory is not based on the facts described, but on the emotional states that the book could have generated at the time of reading. Thus, once the narrative of the story has disappeared, and this or that character has been forgotten, there subsists the breath that maintains the substratum of sensations. There are books, however, whose reading allows us to follow only the simple fact of the narration, despite being able to be deeply documented. Then the memories dissipate and even disappear.

Not all desires are always achievable, there are many and you have to choose, always based on many different factors. This is how over many, many years, now more, now less, Greece appeared and disappeared from my spirit. The seven years that, in addition to other subjects, I spent teaching art history, occasionally stimulated my desire to know those places directly. Because I know the history of art, both Greek architecture and sculpture were no strangers to me, quite the contrary; Knossos, Mycenae, of Athens, Epidaurus, and so many other places were all familiar to me. It was all a naked knowledge of direct vision, a formal knowledge but without the depth of personal experience, of the sensitive touch with the work. In any case I had already been able to contemplate directly a good handful of Greek and Roman sculptures, originals and old copies, in the great museums of Europe: the British, the Louvre, the Vatican. So, in addition to the knowledge provided by the study, it was also possible to see those sculptures directly. For many years the desire to learn more about Greece had been taking shape in my spirit and it was precisely during the spring of 2001, after a trip made through Egypt in February of that year, when I decided to take the next step. Over the next few months I dreamed, planned and lived the trip. I have said many times; I am a dreamer. Don't wake me up. Do no try it, because I don’t want to wake up. I want to dream. I want my death to be a dream too. How could I live without dreaming the dream of life, the dream of desire, the dream of love, the dream that comes from the inside out, the dream that never ends, the dream that nourishes life, the dream that relieves of evils, of laziness, The one does not kill and the one that kills, the one that frees us from others and from oneself, the dream of hopes, of projects, the dream that unleashes the imagination, the chimerical dream, my dream. I arrived at Athen's airport in the evening. The time of day and the drowsiness of the weather did not allow you to see the city from the sky. At the time of landing, four dimly lit lights appeared surrounding a gloomy and unknown space. A half-dismantled taxi began a long journey through streets and more streets, traffic lights right and left, simply chaotic. Like other cities, Cairo, Delhi, among others, Athens is a city where the traffic is absolutely busy, confusing. A few days later, I rented a car to travel freely in Attica and the Peloponnese. The road or highway that leads from southern Attica to the Peloponnese crosses the city of Athens itself. It was, it is true, the rush hour of noon, between twelve and two o'clock, and the bad signage, ignorance of the city, and absolutely chaotic traffic compelled me. After suffering than an the congestion and consequently the immobility that fell on the city for more than an hour, parking the car badly and waiting another hour, until the city began to relax was the best idea before continuing the journey. The hotel was not far from the archeological museum. A well-appointed four-star hotel offered me a spacious room with all kinds of amenities. The dining room was decorated with a fountain from which water gushed with colored light. All in all the most kitsch. A pianist, tired of repeating the same pieces every day, sat in front of a half-tail. World-renowned melody after melody flourished a somewhat melancholy space. Four mis pronounced English words served to wish you a good appetite. Next door, the living room is full of people. Women dressed in half-length dresses were talking loudly. I felt like a protected observer in the middle of that show, rich and vulgar at the same time. |

|---|

The Propylaea |

Next day, early in the morning, I was anxious to embark on the path to the Acropolis, and after a good breakfast I began a winding journey through streets and more streets to, finally, stand in front of the Propylaea feeling the emotions that for years I wanted to experience. With a perspective from below and slowly advancing upward, my chest swelled so I could see that wonder for the first time. The grandeur of the Propylaea revealed the magnificence of the entire Acropolis. Columns and architraves in the purest Doric style showed the austere serenity of that architecture. The day was magnificent and the flutings and the fillets of the shafts of the doric colomnes marked the boundaries between light and shadow. The graphic geometry of Greek architecture that I had taught so many and so many times passed through my mind. That geometry was based on the treatise made by Il Vignola in the 16th century in which he presented a graphic system to represent bases, shafts and capitals of classical architecture.

|

|---|

As soon as you cross the portal, on the right, the magnificent Parthenon was erected. What a wonder !. Despite being in the process of restoration, with scaffolding on either side, the spectacular magnitude of the building ostentatiously showed the balance, the magnificence and the the serenity that for more than two millennia supported the top of its shoulders. The frieze was bare, the tympanum desolate. It is true that dangers of destruction fell on so many wonders, but shouldn't Greece have the right to recover all that the colonizing power plundered? The architecture of the whole structure showed one of the perfect creations of the human spirit. The excitement of the moment along with my personal state of mind helped me to experience one of those hard-to-forget moments. I was in the middle of one of the cornerstones of all Western culture. Personal joy mingled with the irritation of realising that the human race was not able to keep all of those wonders intact. Human interests in each of the different epochs, the hate of this or that religion, unconsciousness and so many other virtues of the evil spirit have allowed the partial or total destruction of many of the creations of the human spirit. At this time I remembered reading that Il Coliseo served as a quarry for the construction of many Roman churches. Damn human barbarism! |

The Parthenon |

|---|

In Phidias' Workshop in Olympia |

In front of me were the spaces that had been traversed by so many characters from ancient Greece since the 5th century BC. Suddenly, and unable to avoid it, my imagination ran wild and allowed me to dialogue with Iktínios and Kallíkratis, among many, many others. From afar I saw Pericles passing with all his retinue. I found Phidias in his workshop in Olympia. What envy! How was a human being able to give birth to that frieze? Will that wonder return to its place of origin?

Detail of the frieze of the Parthenon of Phidias |

|---|

The day was splendid, and the lights of Attica warmed the white marble. Today it may seem unlikely that all that whiteness was covered in the brightest colors. Habit makes us see Greek architecture and sculpture under the purity of the whiteness of marble. I turned around the entire Parthenon. Fences didn't allow me to get close. Better! Thus the perspective, from my point of view allowed the vision of the whole set. I couldn't help but analyze the different parts of the building. Having taught art history forced me to analyze each and every part of the column, the architrave and the tympanum, among others. I counted the number of columns conforming the peristyle, the drums of the shafts, the capitals with each of its parts, the triglyphs and the metopes. I could not free myself from all my knowledge. I know that we cannot present ourselves free from the baggage of knowledge in the face of things or facts and we are submitted to what we are. And we are what we are through a whole process of formation throughout our existence. The freedom of the individual does not exist, we are what we are and we cannot avoid it. Turkish and Venetian pigs whose desire for power with the ignorance of the moment overthrew what we admire today with all its grandeur. Then came the English, plundering right and left, considering themselves masters and lords of the world. The right of the spoils that the mighty believes to have over the weak. The destruction of the pre-Columbian cultures on which the Spanish conquerors superimposed their personal interests of wealth, power and religion passes now through my mind. Considered possessors of absolute values, they had the ability to destroy everything that did not fit their principles: dictatorial power, annihilating, simply savage power. I imagine those armed and soulless conquerors, well, theirs, the cross on the left, the sword on the right. History has been and continues to be a rosary of constructions and destructions. Damn mankind! |

|---|

The Erechtheion |

Surrounded by a clear, Mediterranean sun, the Erechtheion built its slight femininity under the captivating protection of the subjugated caryatids, copies of the ones in the Acropolis Museum, one, however, flown to the British Museum. The perspective of the whole set from a thousand and one different angles offered me one of those states of placidity, seldom and only occasionally attainable. Suddenly, sitting on a rock, ruined by the desolation of time, I found myself conversing with the wise Athenea. I felt neither a speaker nor a poet, nor a philosopher, just a mere mortal enjoying the well-being of the space and time that his company offered me in that place. Was she really a virgin, as the Athenians called her? I didn't ask her. They must have seen her very beautiful to build a temple like the Parthenon and for the great Phidias to cover it with gold and all kinds of ornaments. Who could see her there, in the middle of the Acropolis, showing off all its magnificence! Who knows? Imagine for a second we were transposed into the karmic driven world of reincarnations. Me or you were one of those stonemason workers in the 5th century BC enthusiastically enjoying that image. We could also have been Kallíkratis or Pericles. Let's go further and dive into the dream of having been Phidias himself, or rather, the sculptor's friend, light and shadow, walking early in the morning on a spring, summer or autumn day, holding hands, on the way to the Acropolis, feeling the trembling of the genius a few minutes before facing the hard marble again. Phidias and I, both in love with the wise Athenea, the artist of the model, I of the marble filled with rhinestones.

|

|---|

Over the next few days, I continued to wander through many places in that city: old, old and modern spaces, streets and alleys, museums, and all sorts of spaces and corners full of smells and colors. The pictorial recent life of the city is evolving within the Plaka neighborhood and around Monastikari. Markets, shops of all kinds, small typical taverns, restaurants, all in narrow streets where, inside and out, one breathes, the now noisy, now silent roar of the city. A few days later, a twin-engine propeller plane took off from Athens airport for Crete. The arrival in the sky allowed us to see the brightness of a deep blue sea dotted with pigeons. There, right at my feet, was Crete, beautiful, with mountain-shaped breasts, one of which, Ida, sheltered the first cries of Zeus when, far from his father, he was nursed by the nymph Amalthea. My spirit was in a certain state of excitement produced by the emotion of being able to dive into the maze under Theseus' skin. More and more I felt my heart beating so that I could enjoy for a moment the love of the beautiful Ariadne, a love later abandoned to Dionysus in Naxos. A young woman was waiting for me at the airport. She spoke French with difficulty. We took a taxi to the hotel. Four stars, almost empty. February is the low season in Iraklion. At dinner, two or three badly set tables protruded from about twenty. Two waiters and a couple of maids were moving here and there. They had very little work. One of the waiters, from a low-middle class background, told me that his son was studying at a hospitality school in Iraklion. Obviously, under the influence of the father, a waiter, the son had to reach another level. A few tips loosen lips and raise the spirit.

|

|---|

Ruins of Knossos |

The visit to the ruins of Knossos could not wait long and the next day, with a map in hand and, after asking about the bus station, I set off on roads in a state of deplorable condition with a bus very neglected in the direction of the ruins. Knossos is not far from Heraklion, and if my memory serves me right, after a little over half an hour or three quarters I reached a sparsely populated area. There I boasted, Minos was very close, hidden in one of the thousand rooms of the labyrinth, the royal chamber, well seated on his throne. Every ruin breathes the breath of the past: the grandeur evidenced by the smallness of the present. Much and little imagination requires rebuilding the city-palace of Knossos with the magnificence of large monumental spaces, buildings of all kinds adorned with murals, stone and alabaster plinths, rooms and more rooms, pavements, warehouses and, more and more. One of the features that may surprise us most is the inverted cone-shaped trunk column and a capital with a large flattened throat under an abacus. Knossos is presented to us today disguised as a ruin that emerged from the collapse of more than three millennia. |

|---|

The supposedly easy life in a paradisiacal place, free of fears and walls, makes us think of the placidity of a pleasant and idyllic existence, given to sport and physical beauty, to the bull that, so often represented in the imaginary Minoan, fertilized Pasiphae from which the Minotaur arose. After sitting on the royal throne, I walked around the ruins all day, up stairs, and down them. The sun permeated me from head to toe, and little by little the ruin was transformed by a strong metamorphosis into a magnificent wonderful palace. Suddenly I found myself surrounded by beautifully dressed men and women, flower on their lips, moving from side to side. The columns appeared with a strong chromaticism. The walls looked magnificent frescoes with all sorts of religious and playful ceremonies. An entourage of men, naked torsos and ankle-length skirts carried animals. The women, dressed in skirts wide to the feet, were carrying harps in a sumptuous funeral ritual. Almost without realizing it, I found myself jumping with some athletes on top of big bulls. The enthusiasm and the excitement of the surroundings was absolute. Suddenly a certain melancholy state gently intoxicated me, the dream faded, and I found myself immersed in ruins which, thanks to the reconstructions of Sir Arthur Evans, had enabled me to inhale Ariadne's breath. |

|---|

The supposedly easy life in a paradisiacal place, free of fears and walls, makes us think of the placidity of a pleasant and idyllic existence, given to sport and physical beauty, to the bull that, so often represented in the imaginary Minoan, fertilized Pasiphae from which the Minotaur arose. After sitting on the royal throne, I walked around the ruins all day, up stairs, and down them. The sun permeated me from head to toe, and little by little the ruin was transformed by a strong metamorphosis into a magnificent wonderful palace. Suddenly I found myself surrounded by beautifully dressed men and women, flower on their lips, moving from side to side. The columns appeared with a strong chromaticism. The walls looked magnificent frescoes with all sorts of religious and playful ceremonies. An entourage of men, naked torsos and ankle-length skirts carried animals. The women, dressed in skirts wide to the feet, were carrying harps in a sumptuous funeral ritual. Almost without realizing it, I found myself jumping with some athletes on top of big bulls. The enthusiasm and the excitement of the surroundings was absolute. Suddenly a certain melancholic state gently intoxicated me, the dream faded, and I found myself immersed in ruins which, thanks to the reconstructions of Sir Arthur Evans, had enabled me to inhale Ariadne's breath. |

|---|

And in this city, Iraklion, the distracted walker, wandering the streets without much benefit, arrives at a place where the path climbs up the wall. I do not now know the exact place, north, south, east or west, but there, open to the four winds, a simple tomb emerges, powerful: Nikos Kazantzaki. Emotion swelled in my chest at his grave, even though I had only read one of his works at the time, and that was a long time ago: Alexis Zorba. Under advice, I bought this book from the writer translated into French because I neither knew nor know Greek, the language in which the work is written.

|

|

|---|

It is the individual himself who decides, obviously if he has the capacity, his aesthetic, ethical and moral behavior. Are we aware of what we are looking for? Do we want to satisfy our desires on a material level?. Are we more interested in the pleasure of money? That of artistic creation? The good of others? Throughout a lifetime there are always different stages in which the person ephemerally suffers mutable states, although the personality itself almost always remains constant throughout the journey. It is the ultimate values that we aim to achieve that mark this journey. At a certain point in history, human beings began to reflect on the values that delimit their own behavior and those of others and decided to create laws that determine the behavior of the group and the individual: the code of Hammurabi, the tables of Moses, the laws of Justinian, among others. Kazantzaki defines the novel as a dialogue; the dialogue between the writer and the man of the people, that is, the dialogue between the pen and the great soul of the people. Alexis Zorba is, without a doubt, one of the novels that lingers in my memory. There is the essence of Crete, the synthesis between East and West. The writer has a vision of the present and the future with his eyes always set on the world, the one from here and the one from there, halfway between the two civilizations. Alexis Zorba is not a God, nor a demigod, nor is he a hero, he is a simple human being, a soul wandering in search of pleasure, an individual in constant struggle to maintain freedom in the face of social oppression. Kazantzaki's work is a cry: Every man must cry before he dies. When the writer hears a scream inside him, he doesn't want to drown him to please the dumb and the stuttering. The cry is freedom from others: I don’t want to be a disciple of anyone, I don’t want to have disciples either. His journey in this world is a simple moment, the right time to shout: My soul is a cry and my work is the interpretation of that cry. I, there, sitting on a corner of his tomb, the sky of Crete at the top, heard his pen resound, it was a deep roar from the bottom of the tomb. Alexis Zorba is a character taken from real life. Relying on my memory, I recall that in the book Lletre au Greco, which I also read in French just after my stay in Crete, is where Kazantzaki talks about the real character. A character with whom he was able to share six months in Crete. At this time, writing these words I could not free myself from the desire to rediscover the pages of the book where Kazantzaki describes his encounter with the man. I was struck by the spirit of rereading that five characters throughout his life left a strong imprint on his person: Homer, Buddha, Nietzsche, Bergson and, of course, Zorba. From reading a book, the remains of the sensations generated by the work can survive in the memory in spite of the fact that many of the details that a book must undoubtedly contain can and do often disappear over time. Many of the characters, places and other singular conjunctures that structure its plot have disappeared from my mind, although its memories can be confused with those of the images of the film made from the novel. The memory is always selective, dissipates many of the particularities and other contents and deliver it only to the sensations experienced at the time of reading. There are books that, once the images have been part of the oblivion, there is no feeling left, sometimes not even the pleasure that could have aroused from reading them. A few days ago, here, at the Rodríguez-Amat Foundation where I am living, I had a conversation with two resident artists, both German, Fred Kobecke and Holle Frank, who had read what is still considered a best seller today: The da winci code by Dan Brown. Fred expressed an absolute sympathy for the book, defending the values of erudition and knowledge about the history of art that, among other things and according to him, the novel possesses. Holle, on the contrary, believed that the book was stripped of all literary value, consequently emotional. Both agreed, however, on the strong attraction of reading it: an attraction that made it very difficult to abandon it. The conversation intrigued me and I immediately went to buy the book online. Today, a couple of weeks later, I dived almost up to the middle of the book. My feelings certify my reflection on the work; it is not one of the readings that will remain in my memory. This is a book that, although it has a superficial appeal, is absolutely devoid of any sensitive value. Literary values are limited to creating intrigue, so that the simple reader cannot abandon reading. The language is clear, direct and easily understood, typical, in any case, of a book that seeks solely and exclusively to satisfy the epidermis of a great social mass. There is also the constant and excessive use of indecipherable symbolic and cryptographic games: a good script for a television series. A few days later, from Heraklion, another bus took the route to Messara, the region where the ruins of Faistos are located. I remember that it was in Mires the destination of the bus, from where it was necessary to take another bus, to either Matala or Agia Galini. Although the ruins made a strong impression on me, the feeling was not the same as I had experienced in Cnossos a few days earier. There was only one bus back and it should have passed at a quarter past three, but it didn't. Apparently, when the bus has to leave its origin and there are no passengers, the driver behaves lethargically and, if you want, go on foot. There was no choice but to hitchhike. Four or five cars were enough to start the way back to Mires. A man in his forties, well dressed, very polite, speaking English quite well, told us that this was quite common. For days I had been able to see the strong religiosity of the people on this Mediterranean island, a feeling that had not become apparent to me in Athens. Whether on foot, by car or by bus, many people find themselves passing right in front of a temple, a cemetery or any other religious place. I remember how the man who had hitchhiked us, in addition to revealing a good culture, manifested his strong religiosity in this way, because in the few kilometers that the journey lasted he did the sign of the cross five or six times. He did so just passing in front of a cemetery, a church, or a monastery, of which there are many all over the island. In Arcadia I saw something that also reached my heart. Arcadia is a very mountainous region with dangerous winding roads. When a few days later I drove from Argos to Olympia, after visiting Epidaurus, with a rented car in Athens, on the sides of the road were hundreds of small chapels in which small oil lamps were constantly burning. There is the custom of keeping the oil lamp alive in the chapel. I do not know the system that allows them to perpetuate the light alive, although I must assume that it must be the inhabitants of the area who feed them. In Catalonia, my country, we can find, although not too profuse, flower buds next to a road. Iraklion moves under a purely Mediterranean sun, corners and streets full of history, squares and squares, suddenly a plinth with a bust at the top, a small monument, a bust, wants to represent Domenico Theotocopuli, El Greco. Born in Crete and educated in Venice, the exact place of his birth is not known, but it seems that it was in 1541, as he himself declared in 1606 to be sixty-five years old. Condemned to live in Toledo by imperatives of his time and not in Madrid as he seems to have wished at first. I remember hearing an art history teacher of mine say that El Greco arrives in Spain from Rome, where he is unsuccessful in his attempt to position himself as a painter, attracted by El Escorial. The same professor told us that after painting the dream of Philip II around 1578, the painting was presented to the monarch and he showed no interest for the artist. It is also present in my memory that there were those who placed the creation of this painting around one thousand six hundred and ten. I don’t know the basics that can armor one version or another. Are they, in any case, some of them conforming to reality? It is true that the strength of the mystique of Toledo required some painter to please it, and, like a meteorite falling from the sky, Titian's disciple found the place that allowed him to display his personal mannerisms. His painting darkened over more than two centuries, with no disciples, no followers, and even fewer lovers. The great century and the following one obscured the work of what would be considered again from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is how the appreciation of a creator's work suffers from the shocks of time and individuality. The work of art does not depend solely and exclusively on itself, but, above all, on the receiver, in this case the spectator. In front of me, the work of El Greco is not immutable, it is as fickle as my state of mind. In February of this year, 2006, I was able to see again the set of works in the Prado Museum in Madrid and I was ashamed to see nothing but a set of dirty and screaming dolls. Was it my inability to immerse myself in the work of the painter, or was it my ability not to submit to the recognition established by history? A personal experience, a few years ago, made me think deeply about the dialogue that can be established between the work and the spectator and, consequently, about the appreciation of the work of art. It must first be said that when in the early sixties I discovered the Impressionists and my painting was subjected to the effects of light; the great French masters of the late nineteenth century reached in me the highest values of consideration. In light of this statement, allow me to share with you my experience. Many years later, in February 1997, I was in the National Gallery in London, right in the room of the great Spanish painters of the seventeenth century. There were the Velázquez, the Grecos, the Riberes, the Murillos and so many others. Unaware of the temporality of the experiences of my state of mind, the personal vibration in the face of those works absorbed me from head to toe; the aesthetics of those painters had risen to my head. What sensations! What emotional resonances of mine! I was immersed in the aesthetics of these great Spanish painters. After an indefinite period of experience, I went to the French Impressionist painter's rooms. What a worry! What a dirt! It was very easy for me to understand those bourgeois of the last third of the 19th century who begged pregnant women not to go to see those exhibitions if they didn't want to lose their children. I had to mentalize myself in order to be able to change in myself the parameters that allow us to value a specific aesthetic in order, at least, to be able to re-access dialogue with the painters of the light. One place that had been dancing in my head for years was Súnion; the most far eastern territory of the Mediterranean where the Catalans anchored the flag. The name Súnion will remain in my memory linked to that of a Catalan school where, from 1977 and for five or six years, I carried out a small pedagogical task. Pep Costa-Pau was the creator and promoter. The creator of a modern school with strong pedagogical ideologies: a rigid man, of a strong character, domineering, master and lord of himself. The school, created at the end of the Franco regime, still had to endure the hardships of the dictatorship, but with obstinacy and a desire to serve the country, Pep led a selective and modern school. A couple of years after I had left the school, Pep, coming down from Vilopriu, in the Empordà, where he planned to create the school in the countryside, suffered a fatal accident on the motorway at the height of Sant Celoni. He was a great character and friend. His widow, Magda Planellas, agreed a few years later, in 1994, to join the board of trustees of the foundation I created. |

|---|

Jordi Rodríguez-Amat drawing the temple of Poseidon in Cap Súnion (2002) |

Drawing of the temple of Poseidon of Cape Súnion |

|---|

Súnion has also been forever linked to the Myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Not many years ago I made some drawings about this myth. A man was killing a kind of horned beast. This is a small series of drawings that I was not very happy with. Ariadne's thread is the thread of life, of the labyrinth, of lost and rediscovered spaces, it is the thread of destiny that engraves the imprint of the path, the one of the exit and not the thread of the crumbs of bread along the way, food for sparrows and other small wings. It is also the thread of research and spirit that nurtured the myth of the Cyclades colonizer. Poseidon, on a hot, radiant and powerful suny day, sat on top of a cliff, towards Súnion, to be able to dominate the great marine spaces: the Aegean. Terrible and feared on earth, he was a violent god. The trident, a pagan symbol transformed by Christianity into a diabolical one, and the dolphin accompanied him on his sea voyages to transform into Neptune, whose daughters, supposedly beautiful, were found by my friend the painter Modest Cuixart in the cape from Sant Sebastià in Palafrugell. Many other places, ruins, cities and towns I was able to go through on my journey through Greece. In Mycenae I met Agamemnon, king of Argos, Argolis, or the Peloponnese, and with whom I was able to make the Trojan War, although Jean Giraudoux wished that the Trojan War would not have taken place. Just before the curtain falls Hector says: Elle aura lieu. I would have liked to be Paris to be able to love the beautiful Helena, but there, in the middle of the ruins of Mycenae, once through the great gate of the lions, I had to take sides with the Achaeans, while Homer was hidden under almost three thousand years of history. |

|---|

Jordi Rodríguez-Amat at the exit of the Olimpia stadium Many other memories of that stay come to my mind, including Olympia and Delphi. Allow me to express that one of the images that most strongly impressed me throughout that journey was the Hermes of Praxiteles in Olympia, without a doubt, one of the most wonderful sculptures that my eyes have been able to contemplate. How is it possible to have created a work like this? I have often wondered. How is it possible to have reached the artistic levels of the Greek sculptors of the 5th, 4th and 3rd centuries BC? In my mind today it still presents itself as an impossible reality to explain. Fortunately, Greece remains a well of knowledge: a country, a history, a culture from which the essence of our civilization emerged. |

Hermes of Praxiteles |

|---|

Jordi Rodríguez-Amat 5 de july of 2006 |

|---|

![]() To the Rodríguez-Amat foundation

To the Rodríguez-Amat foundation